Is the Filipino worth the ‘inconvenience’?

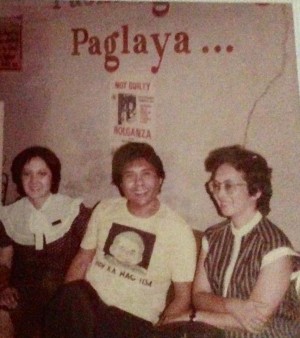

Media executive Rosemarie Holganza-Borromeo (above) shows one of the old newspapers that her late father, Dodong, kept. (CDN Photo/Lito Tecson

by Rosemarie Holganza-Borromeo, Special to Cebu Daily News

Around noon of Christmas Day 1982, as I lay resting on a sofa at home, several hours after our family’s fun-filled noche buena, the sound of loud footsteps roused me from my nap. It was Mommy frantically running down the stairs while listening to the booming voice of a radio announcer with a chilling flash report. My father, Ribomapil “Dodong” Holganza, and eldest brother, Joeyboy, had just been arrested in a rebel “safe house” in the crowded downtown district of Bonifacio and Lopez Jaena Street.

For a 15 year old who had never heard of the word safe house before, the report smelled of irony; but it did not come as a shock. My father had it coming. He was after all, the top leader of Cebu’s anti-Marcos movement who galvanized thousands of Cebuanos to join his so-called Freedom Marches long before the rest of the country took to the streets to unite in protest.

Daddy’s rallies drew national opposition stalwarts like Lorenzo Tañada, Jovito Salonga, Jose W. Diokno, Doy Laurel, Cesar Climaco, Ramon Mitra, Raul Manglapus, Eva Estrada-Kalaw, Joker Arroyo, Aquilino Pimentel Jr., Rene Saguisag and others who appeared to have found a safe haven amongst the throngs of Cebuanos, all freedom-loving descendants of Lapu-Lapu.

The Christmas Day flash report said my father and brother were in a “safe house” with other “rebels.” Oh, the irony of the word, safe house, I thought. There was nothing “safe” about the way we lived our life since Daddy started leading the Cebu opposition in the late ‘70s. And then, that word “house.” What is that? I mean, really.

Young as I was back then, I had lost my concept of a “house” because ours seemed to double as a sanctuary for the hungry and the oppressed who came in droves 24/7 to seek my father’s help.

As Mommy entered the living room with the transistor radio still clutched in her hand, she quickly surveyed the rest of us, as if keeping count of who were left among her loved ones with Daddy and her precious Joeyboy now in military custody. Calmly, she then called the first person she knew could help her, Daddy’s fellow opposition leader and popular radio commentator, Inday Nita Cortes-Daluz, who still had not heard the news then.

Meanwhile, the rest of us stood wondering, what was now going to happen to us. As the AM radio continued blasting reports of the military raid on “Bonifacio Street near Mabini,” I couldn’t help but think that the paradox of Daddy’s life had finally reached its pinnacle.

Named after Philippine heroes RIzal, BOnifacio, MAbini and del PILar, Tatay and Nanay couldn’t have possibly guessed that the real test of the mettle of their youngest son Ribomapil’s character would come in a district named after heroes. Pictures of my father taken moments after their arrest showed him visibly confused though still apparently determined. As he sat on that curb, handcuffed and disheveled, I read the thought that must have raced through his mind then.

Knowing him as I do, he must have figured with neither bitterness nor anger: The Filipino nation is worth this little inconvenience.

Days after their arrest, then Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile flew in to check on their latest catch. Perhaps expecting an apology for being a problem to the Marcos administration, the dictator’s top security officer asked my dad if he was now ready to relent in support of Ferdinand Marcos. Instead, my father recited a litany of Marcos’ sins against the people. That earned him and my brother, Joeyboy, a guaranteed stay in jail for nearly three years with no bail and no trial.

My father was a moderate but back then, there was no room for any kind of protest.

In a letter he wrote from his cell in 1985, he bewailed that while he, my brother and countless others were rotting in jail for crimes that they did not commit, “It is revolting that all around us are people who are truly the enemies of the state, the real subversives who have been subverting the faith and confidence of the Filipinos in our democratic processes, who pillage and plunder the patrimony of this nation, and yet are enjoying their loot and power very well beyond the reach of our anemic, discriminatingly inutile judicial system.”

Always the brilliant political analyst, my father projected in that letter written a year before the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolt that “the oppressed Filipinos have already passed their darkest night, and we are now witnessing the flickering lights of the early dawn of our salvation; that the days of tyranny are about to end; that the wounded tigers in office now roaming and wildly pillaging in the corridors of power may soon be swept away by a flood of an enraged humanity; that true democracy shall be restored from the ashes of a nation torn and shattered to pieces by a reckless and irresponsible leadership; and the Filipinos shall vow that never again shall we let another tyrant rule our beloved land.”

Last January 25, a month short of the EDSA People Power Anniversary this year, my father passed away.

He died knowing that while Filipinos may never again let another tyrant rule over our beloved Philippines, the same political and social ills are still very much around with exactly the same lessons to be learned.

Looking back at Daddy’s sacrifice and how our family suffered for years, I have to ask, without bitterness or anger: Was it really worth all our inconvenience?

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.