TIMELINE: The Cebu Bus Rapid Transit

CEBU CITY, Philippines – Once operational, the bus rapid transit (BRT) in Cebu will be the first of its kind in the Philippines.

After spending nearly two decades in the pipeline, the construction of the much-delayed public mass transportation went full swing in 2023.

But like most big-ticket projects in the country, it hit multiple delays, snags, and design revisions. It was also the subject of several political bickerings to the extent that it was almost completely scrapped.

Recently, another obstacle facing the BRT’s fate surfaced. This one involved calls from the provincial government to halt its construction to protect the heritage status of historical landmarks in Cebu, particularly the Capitol Building and Fuente Osmeña Circle.

READ MORE: Netizens want Cebu BRT construction to proceed: ‘Ipadayun na’

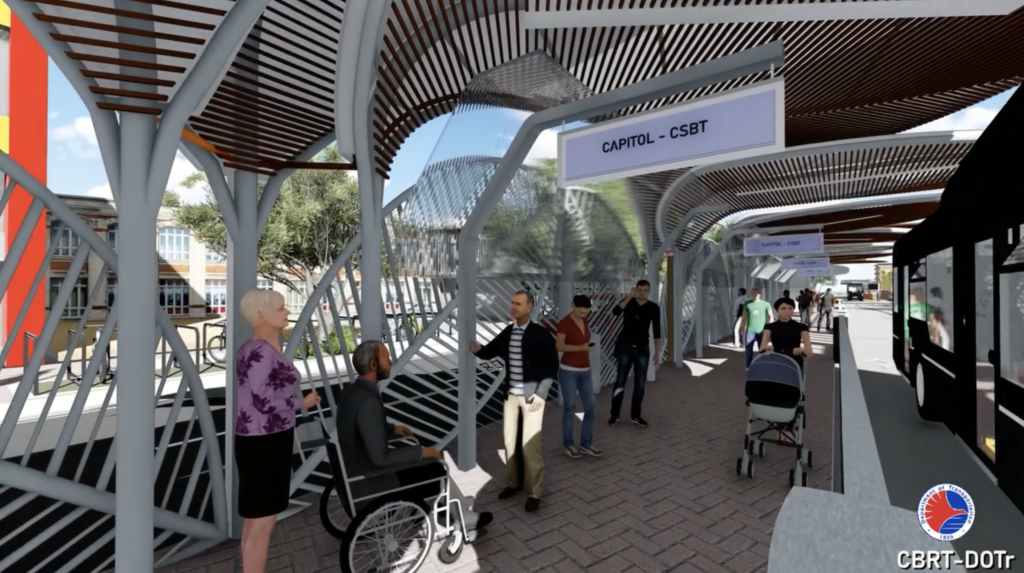

Artist Rendition of the Cebu Bus Rapid Transit, as revealed by the Department of Transportation (DOTr) in 2023. | From DOTr video

The Cebu BRT was just one of the many solutions proposed to solve the perennial issue of traffic congestion here.

The project has stirred controversies as well as discussions not only on traffic. But also on the lack of public transportation, the need to upgrade Cebu’s infrastructure, and how traffic woes ultimately lead to economic losses.

In this article, CDN Digital traces how Cebu BRT came to be – from its introduction to construction, the key developments, and people who played significant roles, both in its actualization and near-demolition.

Introduction: BRT 1990s-2001

Former Cebu City Mayor Tomas Osmeña was credited as the brains behind the Cebu BRT.

Osmeña proposed it in the late 1990s after visiting other countries that have bus-based public transportation like Brazil, where it first emerged.

By the start of the new millennium, and as Cebu City’s economy grew, the then-city government included the BRT as part of its mission to establish a mass transport system.

2008-2009

Formal Planning

But the Cebu BRT was only formally planned in 2008 as it received backing from the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC), the former bureau structure of the now-Department of Transportation (DOTr), and the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT).

The city government, for its part, began proposing the project before global financial institutions like the Public–Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) and World Bank for possible funding.

PPIAF then responded by green-lighting a pre-feasibility study of a BRT in Cebu City, and granted the city funds amounting to $315,000 for it. Their findings turned out positive: a BRT is viable in a metropolis like Cebu.

Visit to Bogota

Aside from national government agencies, the project also gained support from foreign cities like Bogota, the capital of Colombia.

It was in 2009 when former Bogota Mayor Enrique Peñalosa invited Osmeña to visit his city to learn how their BRT system operated.

Bogota’s BRT took off from the Curitiba system in Brazil, which was implemented in the early ’80s.

2010-2013

World Bank support, and first wave of ‘doubts’

A couple of years after official talks started, doubts surrounding the BRT started to appear, with the then-national government initially hesitant to implement it.

But when the late President Benigno ’Noynoy’ Aquino III took the helm of the Malacañan in 2010, hopes of seeing it come to fruition rose back up.

Noynoy’s administration included the BRT in the list of 16 priority projects under their Public-Private Partnership (PPP) initiative.

Additionally, the World Bank stepped in and threw its support for having a BRT not only in Cebu but also in Metro Manila. They committed to fund over $200 million for both BRT systems in the country.

For Cebu, the World Bank would set aside $116 million, $50 million of which was tapped from its Clean Technology Fund (CTF) program.

The city government back then also formed a dedicated team to oversee all concerns related to the planned BRT -from policy-making to right-of-way (RROW).

Cebu BRT original designs unveiled

The first and original design of the Cebu BRT was revealed sometime in 2010, which was also made possible with the help of additional foreign aid from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica).

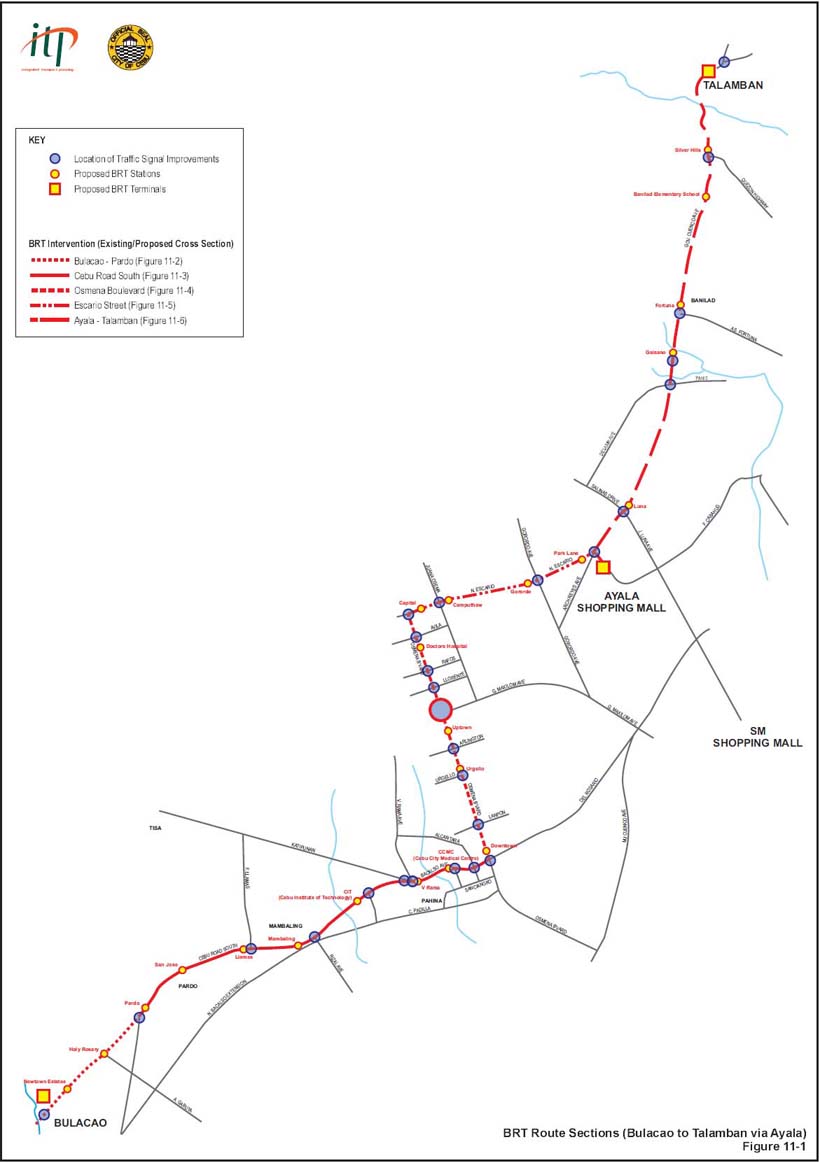

The original route of the Cebu Bus Rapid Transit | Photo from Integrated Transport Planning Ltd

Spanning approximately 22 kilometers, it will connect residents from Barangay Bulacao in the south and Barangay Talamban in the north.

It will have 21 stations, with 10 shelters, and stops along N. Bacalso Avenue, Osmeña Boulevard, Escario Street, Archbishop Reyes Avenue, and M.J. Cuenco Avenue.

Project proponents envisioned acquiring close to 200 buses for the Cebu BRT so it can ferry up to 300,000 passengers in a day.

The BRT was estimated to cost $228.5 million.

If construction of the BRT began in 2010, it would have been already completed fully operational by 2015.

French gov’t support, ICC approval, impact

The French government, through its development bank Agence Française de Développement (AFD), also committed to fund portions of the Cebu BRT in 2012.

BRT(source Colin Brader March 2012)

They pledged around $57 million.

In the same year, the Investment Coordination Committee (ICC) of the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) also approved the implementation of the BRT.

This meant that the project is only one approval away – the one by Neda’s Board itself – from commencing construction.

Meanwhile, most – if not all – stakeholders in Cebu at that time welcomed the idea of establishing a BRT in the capital.

But the proposed public mass transportation system would impact thousands of public utility drivers and lot owners along its routes.

Consultants from the World Bank conducted another feasibility study to determine the scale of the BRT’s impact, including the need for an integrated, city-wide area traffic control system.

In turn, project proponents held a series of public consultations for stakeholders affected – from jeepney drivers to house owners.

2014 – 2016

Neda approval, release of loans, delays

Finally, in 2014, Neda approved the BRT project for Cebu. As a result, development banks like the World Bank and AFD began processing the release of the loans they pledged.

By the next year, 2015, both institutions released their respective loan amounts to the Philippine government.

With the loans already activated, the national government then proceeded to include the construction of the Cebu BRT in the 2016 General Appropriations Act (GAA).

DOTC even issued a notice to proceed.

But despite these developments, the project suffered delays.

These included suggestions to change the BRT’s design and bureaucracy as project proponents went back and forth in accomplishing documentary requirements for the bidding process.

An artist’s perspective of the Bus Rapid Transport project in Cebu City.

When the administration of former President Rodrigo Duterte took over in 2016, the DOTC was disbanded to form two new departments – the DICT and DOTr, the latter now the implementing agency of the Cebu BRT.

The change of leadership in the national government also affected the project’s progress, in what former Cebu City Administrator and BRT project lead, Engr. Nigel Paul Villarete, described as the start of a ’stalemate period’.

2016 – 2019

Duterte admin and calls to scrap

Osmeña was reelected once again as the mayor of Cebu City in 2016.

While his administration drummed up calls to get the Cebu BRT back on track, a national government official vocally and openly wanted it scrapped.

As a result, the project became the subject of a political squabble that ran up to two years.

Osmeña and former Presidential Assistant to the Visayas Michael Lloyd Dino hit at each other over the viability of the BRT.

LRT instead of BRT

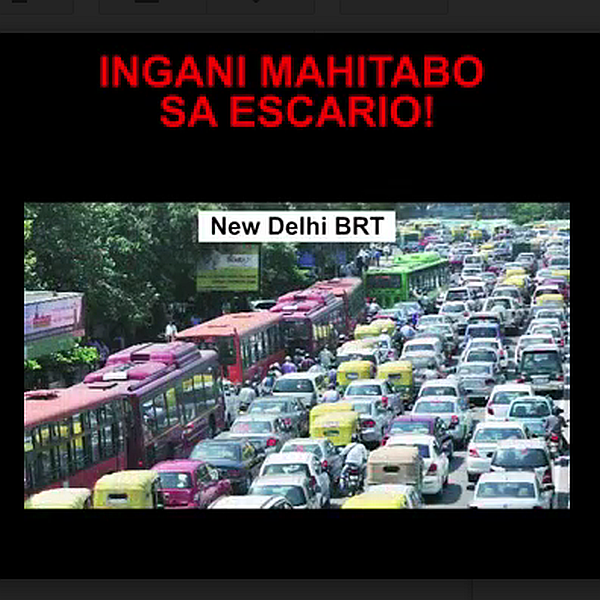

Dino pointed out that the BRT is no longer feasible in the city, citing narrow roads. He also blamed the project for its failure to include road widening in its components.

In turn, the former secretary proposed a more efficient transportation system to better address the traffic congestion in Cebu City, like light-rail transits (LRTs).

Screenshot taken from the video presented by Presidential Assistant for the Visayas Michael Dino in a press conference on Wednesday where he showed Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) projects in Hanoi (Vietnam), New Delhi (India), and Jakarta (Indonesia) failed to address monstrous traffic problems in those Asian cities.

The Regional Development Council in Central Visayas (RDC-7), then headed by designer Kenneth Cobonpue, backed Dino’s calls and urged the national government to abandon it.

More experts and organizations also joined in the debates on whether or not to keep the BRT in Cebu, and it reached its climax in 2018 when the DOTr, with former Secretary Arthur Tugade as its chief, told Neda they wanted to cancel it.

The Neda, which, at this time, already gave the go-signal for the BRT twice, disapproved DOTr’s request.

But Osmeña continued to fight for the BRT, and even warned the national government that bilateral agreements between the Philippines and international institutions would break down should the project be stopped.

IITS

The DOTr revised its stance on the BRT a few months after disclosing its hesitation to have it implemented.

They introduced a new solution to Cebu’s traffic problems, and it’s one where the BRT, cable cars, LRT, and even a monorail would co-exist.

Called the Integrated Inter-modal Transport System (IITS), it was borne out of the DOTr’s inspection of the 23-kilometer BRT route.

2020 – present

Cibus, shortened route

The original proponents of the BRT were shocked when the BRT underwent another round of revisions in its design.

Philippines – The Cebu Interim Bus (CiBus) System that will mimic the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) component of the Metro Cebu Integrated Intermodal Transport System (MCIITS) has started its operations on Monday, March 16, 2020. CDN Digital photo | Raul Constantine Tabanao

The implementing team of DOTr decided to shorten the route – from 23 to 14 kilometers.

Instead at Barangays Talamban and Bulacao, the buses’ terminus points will be limited to the South Road Properties (SRP) and Cebu I.T. Park in Brgy. Apas – a move many did not like, including Osmeña.

In 2020, a few months before the Covid-19 became a global health emergency, officials from the DOTr and local government launched the Cebu Interim Bus (Cibus). Its objective is to mimic the BRT component of IITS.

Rising commitment fees and loan extension

Twelve years since planning began but the BRT has yet to take off, and state auditors at this point already flagged the project multiple times.

The Commission on Audit (COA) urged DOTr, as its implementing agency, to immediately start civil works as the country continued to pay millions in pesos as commitment fees for every year the project was not realized.

A commitment fee is the cost financial institutions like the World Bank levy on borrowers over unutilized loans.

Furthermore, state auditors alerted DOTr that the loan from the World Bank would expire by 2021. Fortunately, the deadline was extended further, with the agency citing the Covid-19 pandemic as another major hurdle in its implementation.

Marcos Jr. admin, groundbreaking

A new President was elected in 2022 but the original proponents of the Cebu BRT have already left the project.

Nevertheless, interests in the BRT renewed when President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. included the BRT in his first State of the Nation Address (SONA), and vowed to have it completed under his watch.

A year later, President Marcos Jr. led the groundbreaking ceremony at Fuente Osmeña Circle, marking the start of the construction for the BRT after being in the pipeline for 15 years.

However, motorists and commuters complained of the inconvenience the BRT brought to their daily lives.

Extension and feeder services

On top of a loan extension, the government also increased its budget for the Cebu BRT due to rising costs.

Artist Rendition of the Cebu Bus Rapid Transit, as revealed by the Department of Transportation (DOTr) in 2023. | From DOTr video

With financial concerns kept at bay, proponents shifted their focus on “improving” the BRT’s design, especially after Cebu City Mayor Michael Rama wanted to reinstate the old route.

In turn, they added feeder services to complement the trunk line of the BRT, ultimately extending its length to approximately 35 kilometers.

These feeder services will ply from Barangays Mambaling to portions of Talisay City in the south, and from I.T. Park to Barangay Talamban.

Basically, the feeder services mimicked the original route that covered the outermost barangays in urban Cebu City.

Calls to stop BRT over heritage laws

Even if construction has begun, discussions on whether to keep the BRT or not reopened after Cebu Gov. Gwendolyn Garcia wanted it stopped for heritage reasons.

After spending more than a decade in the pipeline, construction of the Cebu Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) commenced in 2023. This photo from the Cebu Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) team showed portions of the project near the Cebu Provincial Capitol. It was taken last January 2024,

The governor claimed that civil works of the Cebu BRT along Osmeña Boulevard violated heritage laws after these encroached on the Capitol Building’s buffer zones, a decision that earned the ire of both Rama and Osmeña.

Osmeña even threatened to sue Garcia and reclaim the properties his family donated to the government if the latter insisted on her actions.

Present-time

March 6, 2024

On March 6, 2024, construction continued for the Cebu BRT despite new calls to have it stopped. The DOTr aimed to partially open operations before 2024 ends, and with full operations by 2027.

November 8, 2024

The steel structures along Osmeña Boulevard, which were supposed to serve as foundation for the BRT station near the Capitol, have been removed after Gov. Gwendolyn Garcia ordered their removal, citing safety concerns and road hazards.

Sources:

- Development Projects : Cebu Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Project – P119343. (n.d.). World Bank. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P119343

- INQUIRER.net. (n.d.). Cebu City awaits bus rapid system – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos. Copyright (C) 2001-2008 INQUIRER.net. https://web.archive.org/web/20100921131410/http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/regions/view/20100918-292922/Cebu-City-awaits-bus-rapid-system

- Steering the path | Cebu Daily News. (2017, January 8). INQUIRER.net. https://cebudailynews.inquirer.net/118294/steering-the-path

- Villarete, N. P. (2022, June). The Cebu Bus Rapid Transit Experience. 27th Annual Conference- Transportation Science Society of the Philippines (TSSP), Philippines. https://ncts.upd.edu.ph/tssp/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Cebu-Bus-Rapid-Transit-BRT-Experience.pdf

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.