accounts of this.

Luke has but a brief narration of Jesus’ baptism. He introduces it with the people’s curiosity as to the identity of John, whether he might be the Messiah. John told them in reply, “I am baptizing you with water, but one mightier than I is coming. I am not worthy to loosen the thongs of his sandals. He will baptize you with the holy Spirit and fire.”

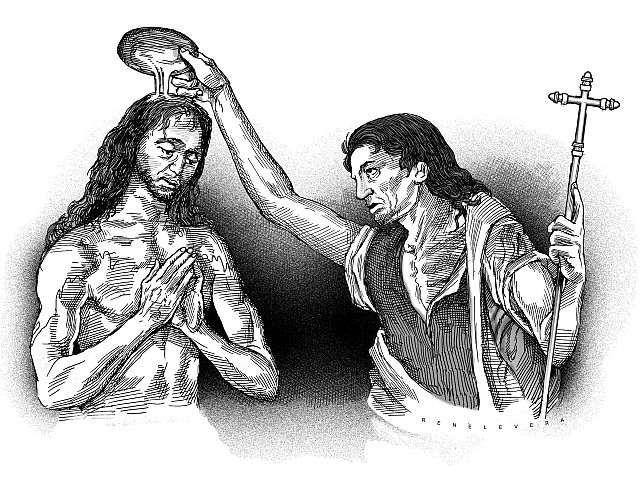

Luke merely mentions the baptism of Jesus in passing, giving the emphasis to that which happened subsequent to the same: “After all the people had been baptized and Jesus also had been baptized and was praying, heaven was opened and the holy Spirit descended upon him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased.’”

Verrocchio’s painting shows us the actual baptism. It depicts John pouring water on Jesus’ head, above which hovers a dove, the Holy Spirit. We notice, however, the presence of two pubescent angels to the right of Jesus. If we find the painting engaging, it is because of the angel furthest to the left, the one who is kneeling.

Verrocchio ran a large workshop in Florence. Among his apprentices were Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo joined Verrocchio’s workshop at age 23, and, when a church commissioned Verrocchio to do the work in question, Leonardo contributed to it by painting the angel. Interest in the angel grew, not just because Leonardo went on to become a great artist, but also because already the figure exhibits the marks of Leonardo’s genius – the tumbling bright locks, the expressive eyes, the sweet and delightful face. In comparison, the other angel looks tired.

Verrocchio did not actually relish painting and instead found his niche in sculpture and metalwork. The legend goes that, when Verrocchio saw Leonardo’s angel, he felt humbled by the fact that an apprentice of his could surpass him, and did not touch the paint brush ever again.

In fact, being gormless about art history, I would have not known about this if a friend did not gift me with a reproduction, not of the entire Verrocchio painting, but just a detail of it, the one depicting Leonardo’s angel.

If Verrocchio’s “The Baptism of Christ” were a photograph, apart from the fact that its presence there was for a sincere purpose, Leonardo’s angel might be called a “photobomb” – which normally refers to “a person or thing unexpectedly appearing in the camera’s field of view as the picture is taken,” which changes the mood of the photograph, usually into something hilarious.

At one time, when I checked a photograph of myself taken in the garden, I saw a white rooster behind, so positioned as to seem to be standing on my right shoulder. Many people liked the photograph because of the rooster, not because of my pose, which tried to approximate that of George Bernard Shaw with his clothes on.

I now consider that rooster a gift. I presume that Verrocchio must have treated Leonardo’s angel in the same manner, although it might have made him, however slightly, envious of his young apprentice’s skills.

When I consider the larger picture of life, how often do I find there the presence of someone or something unexpected, which somehow adds to its meaning and beauty. It was as though I were an artist doing a painting, and then, without notice, someone else, a Leonardo, added a detail to it, which transforms it into something utterly precious. This I call grace.

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.