For the next one, a shepherd named Manolios is picked to play Christ, and as apostles Yannakos (Peter), Michelis (John), Panayotaros (Judas), to name just three. The widow Katerina, the village prostitute, plays Mary Magdalene.

The village elders, steered by a priest, Grigoris, make the selection. All this within earshot of the Turkish Agha, overlord of Lycovrissi, who lives a dissipated life, drinking raki and doting on pretty boys.

In time, as they prepare for the event, Manolios and company undergo a change and themselves become the characters assigned to them. Grigoris himself turns into Caiaphas, as the story unfolds, and the Agha into Pontius Pilate.

What brings this about is the arrival of a group of Greek refugees, dying from illness and lack of food, whose village was overrun by Turks and who are brought into Lycovrissi by another priest, Fotis. The domineering and egotistic Grigoris, sensing a potential rival, orders the refugees to move on, and tells the people, when a woman collapses and dies from hunger, that she expired from cholera, to get the villagers to side with him.

Fotis and his band take refuge in the caves of a nearby mountain.

Manolios, having been chosen to portray the role of Christ, considers himself a different man. He persuades others to join him in helping the refugees. They steal food from the village leader’s cellar to feed the women and children. Grigoris is enraged. And, of course, the village leader too.

When his favorite youth is found murdered in his bed, the Agha arrests the elders, threatening to hang one of them every day until the killer is surrendered. Manolios believes that he must sacrifice himself and falsely own up to the slaying. The real killer happens to be a member of Agha’s household.

Manolios ends his engagement to a woman and retreats to the hills to live an ascetic life. There he is joined by Michelis.

True to form, Panayotaros, who is assigned the role of Judas, spies and reports on them to Grigoris.

In the end, a mob kills Manolios, instigated by Grigoris, who eggs Panayotaros on, and the latter, addressing Grigoris, sticks the dagger into Manolios, saying, “With your blessing, Father.”

Fotis and his group carry the dead body of Manolios to their mountain. Kneeling next to the body, Fotis says, “Two thousand years have gone by and men crucify You still. When will you be born, my Christ, and not be crucified any more, but live among us for eternity.”

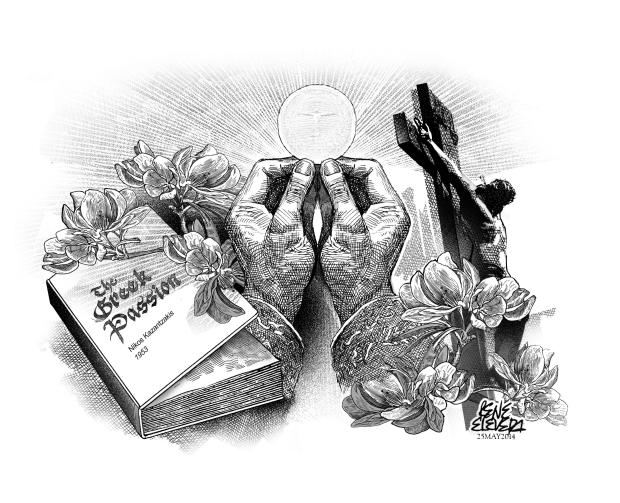

Kazantzakis speaks of a process in which “matter is transubstantiated into spirit.” There is something Eucharistic about the phrase – in Catholic thought, transubstantiation is how the bread and wine offered in the Mass become the body and blood of Christ.

Insofar as Kazantzakis’ novel parallels the Passion of the Lord, from which the Mass draws its graces, it somehow illustrates that transubstantiation.

Whatever its flaws, the story speaks of truths that the world, people by such as Grigoris, the Agha and Panayotaros, cannot understand, which truths are set out in the Beatitudes, and for which Christ died on the Cross. These truths are revealed only by the Spirit, which, before his ascension, Jesus promised to his disciples: “I shall ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate to be with you forever, that Spirit of truth whom the world can never receive since it neither sees nor knows him.”

For as long as the world does not see or know the Spirit, men will continue to crucify Christ, who lives in his Body, the Church, and identifies himself with its members, especially the miserable and the suffering.

As John Steinbeck puts it, “An unbelieved truth can hurt a man much more than a lie. It takes great courage to back truth unacceptable to our times. There’s a punishment for it, and it’s usually crucifixion.”

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.